"An Iranian Moment: A Convergence of Art and Politics"

By Shiva Balaghi | Guggenheim

6 January 2017

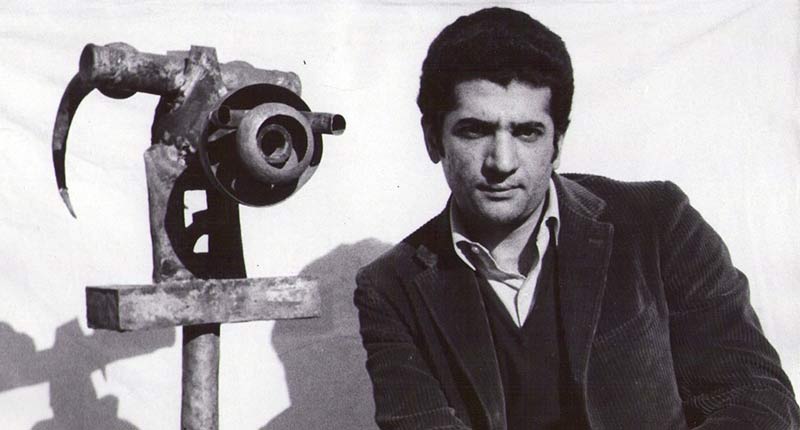

They called it the Persian Spring. Through a historic confluence in the spring of 2015, three American museums held major monographic exhibitions of Iranian art simultaneously. The Davis Museum at Wellesley organized a six-decade retrospective of work by Parviz Tanavoli, Iran’s leading sculptor.1 An exquisite show of Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian’s mosaic mirror works and line drawings traveled from Serralves to the Guggenheim Museum in New York.2 And Shirin Neshat’s photographs and video installations were exhibited at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C.3 Boston Globe critic Sebastian Smee wrote, “An Iranian moment? It almost feels like it.”

As museum audiences were absorbing all this Iranian art, another historic turn of events was unfolding in the diplomatic arena—at various intervals between February and July, the P5+1 negotiations to curb Iran’s nuclear program took place in Vienna. After years of false starts, the final stretch of the talks unfolded in dramatic fashion. The world press congregated in Vienna, reporting the minutia of the negotiations between foreign ministers from seven countries as they hammered out the final agreement. There were reports of all-night negotiations fuelled by Nespresso and room service. During news blackouts, reporters kept vigil outside the balconies of the famed Coburg Palace, where diplomats would step out from time to time to get some fresh air and mug for the paparazzi.

The parallel stories of diplomatic and artistic exchange between the United States and Iran are intertwined in some fascinating ways. Tanavoli, Farmanfarmaian, and Neshat are all artists who have lived and made art in the interstitial spaces of Iran’s relations with the States, spaces that have expanded and retracted intermittently since the end of World War II. As one of the curators of the Tanavoli exhibit, I often checked in with him in the weeks leading up to the show. One night over the phone, he told me in a quiet voice, “the doors have finally opened.” Just before his opening, I walked with him through the galleries of the Davis, looking at his sculptures, drawings, and paintings. He spoke again of how his art was inspired by Persian poetry and folk art but imbued with a pop sensibility—a result of his having been exposed to it when living in the States in the 1960s. I asked him to explain further his comment on doors opening. A view of Parviz Tanavoli’s first U.S. museum retrospective at the Davis Museum at Wellesley College in February 2014.

“With the background I had in the U.S.,” Tanavoli told me, “I expected that the doors would never close on me, because from a very young stage in my career, I had shows in the States. I created a lot of my work in the U.S. I taught at the Minnesota College of Art and Design. I had a following in the public in the U.S. I was known there. Then all of a sudden, with the Iranian revolution and the war and the hostage crisis, they closed all the doors. The relations between the two countries were tarnished, and I couldn’t continue. I lost all my connections. I went into the dark.” The Davis exhibit was the first solo exhibition of Tanavoli’s work in a U.S. museum in nearly four decades.

Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian first arrived in the United States by boat in 1944. She studied at Cornell and the Parsons School of Design. For a time, she worked as a fashion illustrator, designing the famous Persian violet logo for Bonwit Teller department stores. Monir tapped into New York’s lively cultural circles, interacting with Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Joan Mitchell, and Mark Rothko. Returning to Iran in 1957, she rediscovered the country with renewed vigor, finding inspiration in its tribal arts and rugged landscapes. As her close friend Frank Stella explained, Monir’s art combines “the measured geometry” of Western abstraction with the underlying concepts and designs of Islamic architecture.5 In Islamic cosmology, each geometric shape has a symbolic value. For Monir, the hexagon became a resonant shape with which she could create infinite possibilities. Monir told me that as a young artist in New York she would often pass the construction site along Central Park on her evening strolls, watching the Guggenheim Museum being built. Decades later, at the age of 92, she would become the first Iranian artist to receive a solo exhibition at the museum.

At the Hirshhorn, the convergence of history and art became the curatorial impulse for Shirin Neshat’s exhibition, “Facing History.” Alongside Neshat’s art, the museum exhibited archival photographs and news footage that the artist used as source material for her films, photographs, and video installations. “I am so proud, as a woman artist, to be taking up so much space at the Hirshhorn,” Neshat told viewers at the opening. As she completed her remarks, I looked over at crowds of museumgoers and watched as a father holding his young daughter’s hands carefully showed her the historical materials relating to the 1953 coup in Iran, a U.S.-led action that overthrew the democratically elected government of Prime Minister Mossadegh. The exhibition offered an artistic interjection on the troubled histories of Iran’s relations with the States. By July 14, 2015, it seemed a new chapter was being opened in that troubled history. President Obama spoke to the nation, announcing that following two years of negotiations, a comprehensive deal had been reached with Iran. “Our difference are real and the difficult history between our nations cannot be ignored,” Obama said. “But it is possible to change.” After decades of retrenchment, political and cultural flows between Iran and the U.S. are fundamentally shifting. And for Iran’s artists, the doors are once again opening.