"Iran uses Canadian citizens as pawns in tense political game"

By Daphne Bramham | Vancouver Sun

12 July 2016

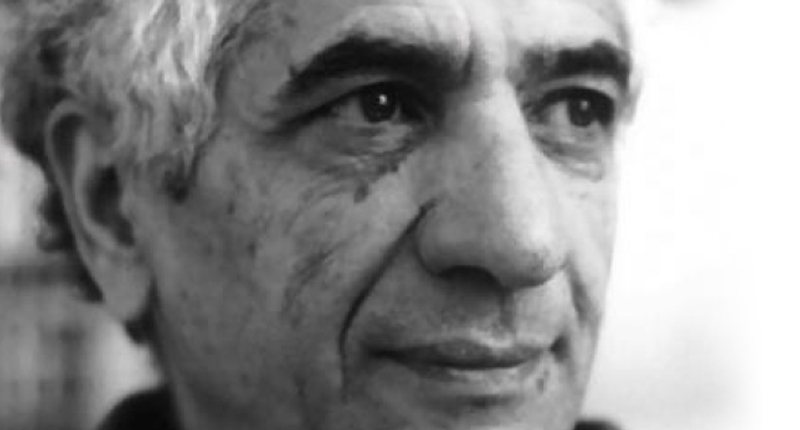

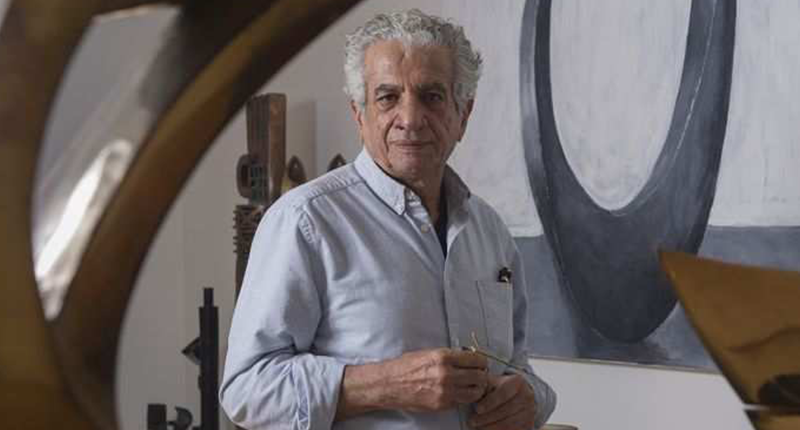

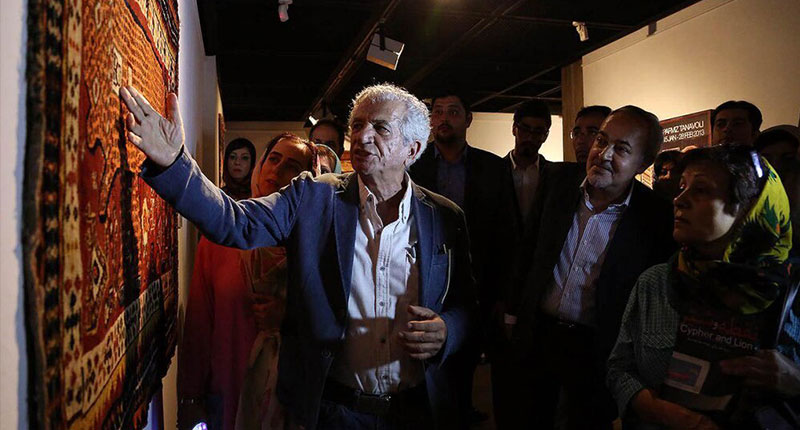

Sculptor Parviz Tanavoli and anthropologist Homa Hoodfar are dual citizens and pawns caught up in a web of political tensions as Canada and Iran take tentative steps to re-establish diplomatic relations.

In Iran, there’s the perennial tug of war between hardliners — who control the judiciary, police and Revolutionary Guard — and moderates. Recently, the hardliners have suffered three key defeats. They lost the 2013 presidential election and recent parliamentary elections. And, last year, they were unable to stop the recent international nuclear accord.

As a result, the hardliners are “bruised, defeated and angry,” says Nader Hashemi, a Canadian who is an associate professor and director for the Center for Middle East Studies at the University of Denver. By detaining dual nationals, he says the hardliners send a strong message both to outsiders and to Iranians that they still have power to intimidate and disrupt.

Here, reopening the Tehran embassy was a Liberal election promise that met with widespread approval within the 160,000-strong Iranian-Canadian community.

The detentions pose an almost existential dilemma for Canada and Prime Minister Justin Trudeau of values (human rights, democracy) against political and economic interests.

Canada could make continuing talks aimed at renewed diplomatic ties conditional on Tanavoli’s and Hoodfar’s release. But if Canada does, what will Iran ask in return because there will be a quid pro quo just as there was in the lead up to the nuclear deal when the United States swapped seven Iranians for four Iranian-Americans (including Washington Post reporter Jason Rezaian)?

Among the complicating factors is that Canada is providing equipment and military training to Kurds in Iraq near the Iranian border, where there has long been a Kurdish secessionist movement.

The very fact that Canada has no diplomatic presence — no people there who have built relationships with key Iranian leaders — makes this calculation of values versus interests more difficult.

Since the Harper government declared Iran a state sponsor of terrorism in 2012 and abruptly closed the embassy, Canadian interests have been looked after by Italy. So, it’s Italians who are providing whatever limited consular services they can to Tanavoli and Hoodfar as well as intelligence to the Canadian government.

For now, it’s Hoodfar, the 65-year-old retired Concordia professor, who is in the most danger. She has a rare neurological disease for which she’s had no treatment since being jailed June 6 in the notorious Evin Prison. That’s where 13 years ago Iranian-Canadian photojournalist Zahra Kazemi was tortured and killed.

Why she’s being held, no one is saying. All that the Iranian prosecutor has said is that she will soon be charged along with three others: Iranian-American businessman Siamak Namazi; Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe, an Iranian-British woman working for Thomson Reuters Foundation, the news agency’s charitable arm; and Nizar Zakka, who is Lebanese and a permanent resident of the United States who has worked for the American government.

Tanavoli, so far, remains free within Iran and continues to have both email and cellphone access. But on July 2, he had his passport confiscated and was stopped from boarding a plane to London where he was to speak at the British Museum about his work and his new book.

The 79-year-old was told late last week that he will be indicted for “disturbing the public peace.” It’s not clear whether the “disturbance” is related to his sculptures or to his latest book about late 19th and early 20th-century images of European women in Persian households. The book’s cover image is of a European woman whose nipple is barely visible under a diaphanous robe.

What makes the detention of the two Canadians so hard for their families and friends is the arbitrariness of it. Neither Tanavoli nor Hoodfar has been involved in political protests or written anti-government tracts. Throughout their careers, both have worked hard to promote and explain the beauty, history and complexity of the Iranian society. It’s why neither felt concerned about traveling on their Iranian passports and returning to Tehran.

Tanavoli, in particular, has been making frequent trips back for more than a decade. Among the reasons he went this time was to prepare for a fall exhibition of his sculptures in Tehran.

“A campaign of well-known artists, writers, musicians and cinematographers are on (a) move to get me out of this,” Tanavoli wrote to me in an email Tuesday. “I have good lawyers and they are confident it will be sorted out soon.

“Having said all this, I just have to wait and see.”

This arbitrariness, the fear that it engenders and the often brutal treatment of those who fall victim to it are hallmarks of an authoritarian and unreliable government.

More so than the Saudi Arabian weapons sale, how Trudeau handles the detention of Canadian citizens will test his mettle and his values.