"Iranian artist Tanavoli in the spotlight at Davis Museum"

By Amelia Smith | Middle East Monitor

3 February 2015

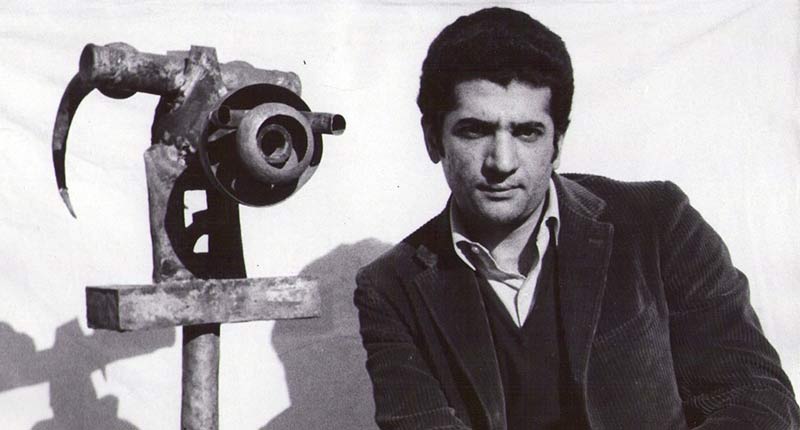

Parviz Tanavoli, with “Big Heech Lovers” (2007).

As a young boy Parviv Tanavoli’s favourite toy was the simple lock. As there were no ready-made toys like those of today he would take them apart, fix them and make keys for the ones that didn’t work. “I was the locksmith of the neighbourhood because all the locks in those days had one key and they were handmade. There weren’t that many machine-made locks. If there were they were very expensive,” he tells me. Later Tanavoli went to Italy to study. It was on his return, he recalls, that he realised the role locks played in Shia Islam and Persian culture. In Iran public water houses were built in bazaars and neighbourhoods and during the hot summers passers-by would stop to take a sip of water. Gradually people started to make donations and the water houses became shrine-like decorated with imagery of the imams.

“People who have wishes or problems go to the shrines and tie up a strip of their clothing or fasten a lock to the grille of the shrine hoping that they can unlock their problems and cure their sicknesses or disease,” explains Tanavoli. “So the lock has great significance in Persian culture.”

In the sixties the lock became one of the iconographies central to a new movement co-founded by Tanavoli, termed Saqqakhneh, the Farsi word for water house. Dubbed spiritual “pop art”, Saqqakhneh sought to incorporate Shia symbols into art and often you will see padlocks on the body of Tanavoli’s sculptures and in the work of the young artists that joined the movement.

Another concept central to Tanavoli’s work is the principle of “Heech”, Farsi for “nothing”. Like the lock, the word Heech has been moulded by the artist and incorporated into the anatomy of his sculptures numerous times. It began in 1965, he says, in protest to the popularisation of calligraphy that at the time became fashionable and was exhibited in nearly every gallery. “I gave calligraphy up and only used one word,” he says.

Tanavoli describes the shape of Heech as malleable and soft, a word that can be put in a cage or on the walls. “I found there is so much in the Heech, that Heech is not nothing, Heech is something. Then later, as time went on, I realised that there is so much meaning behind it and so many poets prior to me, from centuries ago, have paid attention to this word and have used it and that is how it began.”

The early poets, Rumi, Khayyam and Hafez, wrote a lot about Heech, points out Tanavoli, and posed the question of whether existence is nothing or whether non-existence is existence. “They wanted people to think about that – don’t underestimate the nothingness. As important as existence and thing are, no thing or nothing is important too.” Work that features the Heech is the most popular and sought after of Tanavoli’s art. He says this is because people can relate to it and find something in the concept they can connect to. “It’s a simple shape, it’s abstract, and it’s very meaningful. It has a sculptural body different than other known sculptural figures,” he reflects. “I think there are many reasons it became popular.”

In 2008 Tanavoli’s The Wall (Oh Persepolis), a two metre bronze sculpture etched with hieroglyphics, made a record sale when Christie’s auction house sold it for $2.84 million, the highest ever paid for a piece of artwork from the Middle East. Despite this, Tanavoli says that commercial success has not compromised his work. “I didn’t follow the market or market requests, in fact I turned it down in many instances and I followed my path. I continued doing my thing and opted out. I haven’t changed, I haven’t really commercialised any of my art.”

Though Tanavoli would not describe himself as “political”, there is certainly a political element to some of his work. Most artists, he says, are somehow involved in the politics of their time. “All the artists I know somehow are, but they may not reflect it directly, they might be very indirect. Somehow artists stay away from it especially in the area that we live. It’s not very safe to be political.”

Heech in a Cage – literally a Heech coming out of a silver cage - was made in protest of Guantanamo Bay detention camp in Cuba, a facility set up to imprison and interrogate suspects in the “war on terror”. The prison has attracted worldwide controversy for its use of water-boarding, the force-feeding of prisoners on hunger strike and detention without trial.

“I was very bothered when they put all these people in jail without giving them a fair trial. The torture and the way they were kept. I always felt that even if there are innocent among them, this is damaging American democracy. I decided to make a monument to the innocents of the Guantanamo.”

The monument was intended to be an enlarged version of Heech in a Cage which would then be donated to the people of Afghanistan; Afghanis were once the largest nationality represented in Guantanamo. However, Tanavoli couldn’t find a sponsor or a location in Afghanistan willing to take it, and so the project was never realised. Closer to home Tanavoli has been involved in a drawn out conflict with the local government. In 2002 the artist’s house was turned into a museum by request of the city of Tehran with the backing of then Mayor Mohammad-Hassan Malekmadani who was keen on art and culture. But when Ahmadinejad became mayor he closed the museum declaring “it wasn’t part of our culture it was foreign culture,” recounts Tanavoli.

The artist went to court and fought for six years to get his house back but by this time much of his artwork had been taken. Last March he retrieved 13 pieces through a court order, but a few days later people from the municipality hired trucks and cranes, came back, broke the door down and took everything again.

“They don’t like my work, they’re not even interested,” he says. “But now they have realised that it is worth some money and that’s all they’re interested in. I wish they had even taken care of it. Several of my works are broken, some are damaged, some kept in very bad conditions and not handled professionally and so they are going into a state of decay. I want to get them back. I don’t know if I will or not, I still haven’t given up.”

Tanavoli says that wide-spread censorship on art and culture is more relaxed than it was in the Ahmedinejad years, under whom hundreds of books were censored, publishing permits were denied, films were banned and theatres shut down. “It was the worst period of all these eight years,” he reiterates. “Things are loosening now, they are better and of course more books are published, films are shown and theatres are again going back to their lives. So it goes up and down.”

Though he has a studio and a house in Tehran, Tanavoli and his family moved to Canada in 1989 and now lives and works between the two countries. “I couldn’t sell my sculptures there. I wasn’t even allowed to sell my sculptures there,” he says, explaining why his family moved. “Our children had to go to college for higher schooling and they didn’t have any chances, especially the girls. We have two daughters, so we decided to move to Canada for the sake of the children and then also to re-start my life. It wasn’t easy but of course things are better now.”

A decade before his move Tanavoli retired as head of the sculpture department at Tehran University, at the time of the Islamic Revolution.

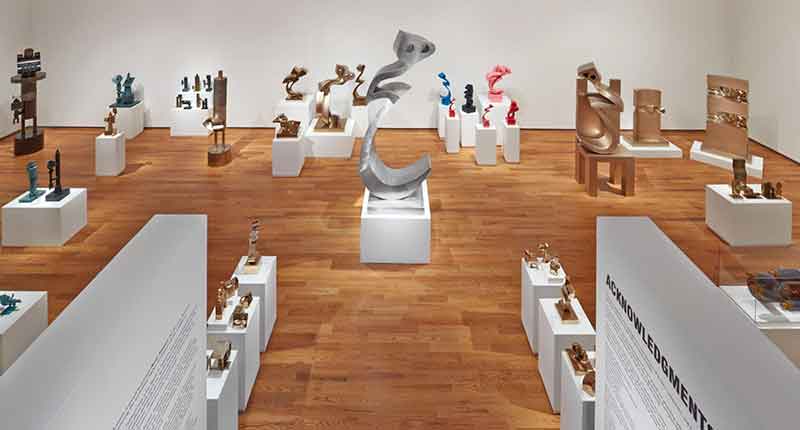

Tanavoli’s work can be found in private and public collections from the British Museum in London to the Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art in New York. At the beginning of February a retrospective of Tanavoli’s work will go on display at the Davis Museum, Wellesley College in the US where over 175 of his pieces will be exhibited. Tanavoli says it will be a good opportunity for Americans to experience Iranian culture which often gets lost in news reporting from such a volatile region.

“I am very happy this is happening, especially in the States, because of this embargo and lack of communication,” says Tanavoli. The US placed sanctions on Iran following the US embassy seizure in 1979 and has maintained them, and broadened them, for most of the period following this.

“I think this might open the door. Americans have the right to see the other side of our culture; I mean the cultural part not just all this bad news. Of course the embargo has stopped all of this for a long time. So this is a good time, a good period, and I’m very much looking forward that there is going to be communication through art and Americans can see a taste of the art of Iran and myself and that part of the world.”